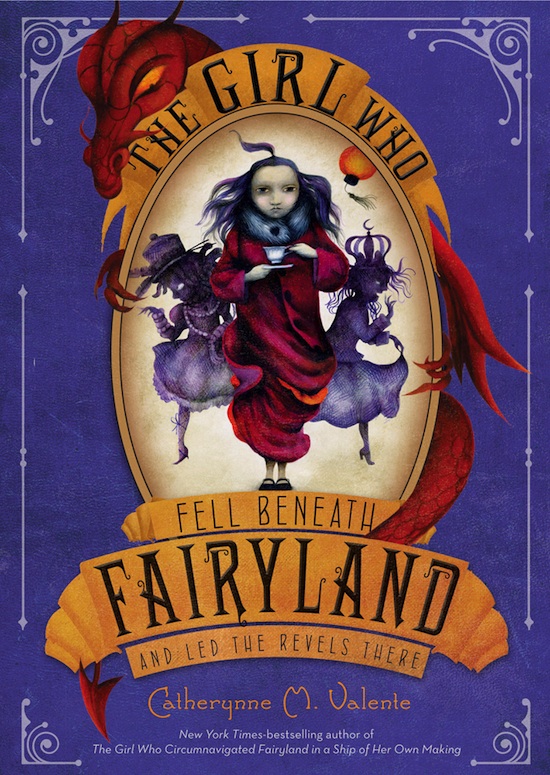

All this week we’re serializing the first five chapters of the long-awaited sequel to The Girl Who Circumnavigated Fairyland in a Ship of Her Own Making, Catherynne M. Valente’s first Fairyland book — The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revels There is out on October 2nd. You can keep track of all the chapters here.

September has longed to return to Fairyland after her first adventure there. And when she finally does, she learns that its inhabitants have been losing their shadows—and their magic—to the world of Fairyland Below. This underworld has a new ruler: Halloween, the Hollow Queen, who is September’s shadow. And Halloween does not want to give Fairyland’s shadows back.

Fans of Valente’s bestselling, first Fairyland book will revel in the lush setting, characters, and language of September’s journey, all brought to life by fine artist Ana Juan. Readers will also welcome back good friends Ell, the Wyverary, and the boy Saturday. But in Fairyland Below, even the best of friends aren’t always what they seem. . . .

CHAPTER II

SHADOWS IN THE FOREST

In Which September Discovers a Forest of Glass, Applies Extremely Practical Skills to It, Encounters a Rather Unfriendly Reindeer, and Finds that Something Has Gone Terribly Awry in Fairyland

September looked up from the pale grass. She stood shakily, rubbing her bruised shins. The border between our world and Fairyland had not been kind to her this time, a girl alone, with no green-suited protector to push her through all the checkpoints with no damage done. September wiped her nose and looked about to see where she had got herself.

A forest rose up around her. Bright afternoon sunshine shone through it, turning every branch to flame and gold and sparkling purple prisms—for every tall tree was made of twisted, wavering, wild, and lumpy glass. Glass roots humped up and dove down into the snowy earth; glass leaves moved and jingled against one another like tiny sleigh bells. Bright pink birds darted in to snap at the glass berries with their round green beaks. They trilled triumph with deep alto voices that sounded like nothing so much as Gotitgotitgotit and Strangegirl!Strangegirl! What a desolate and cold and beautiful place those birds lived in! Tangled white underbrush flowed up around gnarled and fiery oaks. Glass dew shivered from leaves and glass moss crushed delicately beneath her feet. In clutches here and there, tiny silver-blue glass flowers peeked up from inside rings of red-gold glass mushrooms.

September laughed. I’m back, oh, I’m back! She whirled around with her arms out and then clasped them to her mouth—her laughter echoed strangely in the glass wood. It wasn’t an ugly sound. Actually, she rather liked it, like talking into a seashell. Oh, I’m here! I’m really here and it is the best of birthday presents!

“Hullo, Fairyland!” she cried. Her echo splashed out through the air like bright paint.

Strangegirl! Strangegirl! answered the pink-and-green birds. Gotitgotitgotit!

September laughed again. She reached up to a low branch where one of the birds was watching her with curious glassy eyes. It reached out an iridescent claw to her.

“Hullo, Bird!” she said happily. “I have come back and everything is just as strange and marvelous as I remembered! If the girls at school could see this place, it would shut them right up, I don’t mind telling you. Can you talk? Can you tell me everything that’s happened since I’ve been gone? Is everything lovely now? Have the Fairies come back? Are there country dances every night and a pot of cocoa on every table? If you can’t talk, that’s all right, but if you can, you ought to! Talking is frightful fun, when you’re cheerful. And I am cheerful! Oh, I am, Bird. Ever so cheerful.” September laughed a third time. After so long keeping to herself and tending her secret quietly, all these words just bubbled up out of her her like cool golden champagne.

But the laugh caught in her throat. Perhaps no one else could have seen it so quickly, or been so chilled by the sight, having lived with such a thing herself for so long.

The bird had no shadow.

It cocked its head at her, and if it could talk it decided not to. It sprang off to hunt a glass worm or three. September looked at the frosty meadows, at the hillsides, at the mushrooms and flowers. Her stomach turned over and hid under her ribs.

Nothing had a shadow. Not the trees, not the grass, not the pretty green chests of the other birds still watching her, wondering what was the matter.

A glass leaf fell and drifted slowly to earth, casting no dark shape beneath it.

The low little wall September had tripped over ran as far as she could peer in both directions. Pale bluish moss stuck out of every crack in its dark face like unruly hair. The deep black glass stones shone. Veins of white crystal shot through them. The forest of reflections showered her with doubled and tripled light, little rainbows and long shafts of bloody orange. September shut her eyes several times and opened them again, just to be sure, just to be certain she was back in Fairyland, that she wasn’t simply knocked silly by her fall. And then one last time, to be sure that the shadows really were gone. A loud sigh teakettled out of her. Her cheeks glowed as pink as the birds above and the leaves on the little glass-maples.

And yet even with a sense of wrongness spreading out all through the shadowless forest, September could not help still feeling full and warm and joyful. She could not help running her mind over a wonderful thought, over and over, like a smooth, shiny stone: I am here, I am home, no one forgot me, and I am not eighty yet.

September spun about suddenly, looking for A-Through-L and Saturday and Gleam and the Green Wind. Surely, they had got word she was coming and would meet her! With a grand picnic and news and old jokes. But she found herself quite alone, save for the rosy-colored birds staring curiously at the loud thing suddenly taking up space in their forest, and a couple of long yellow clouds hanging in the sky.

“Well,” September explained sheepishly to the birds, “I suppose that would be asking rather a lot, to have it all arranged like a tea party for me, with all my friends here and waiting!” A big male bird whistled, shaking his splendid tail feathers. “I expect I’m in some exciting outer province of Fairyland and will have to find my way on my lonesome. The train doesn’t drop you at your house, see! You must sometimes get a lift from someone kindly!” A smaller bird with a splash of black on her chest looked dubious.

September recalled that Pandemonium, the capital of Fairyland, did not rest in any one place. It moved about quite a bit in order to satisfy the needs of anyone looking for it. She had only to behave as a heroine would behave, to look stalwart and true, to brandish something bravely, and surely she would find herself back in those wonderful tubs kept by the soap golem Lye, making herself clean and ready to enter the great city. A-through-L would be living in Pandemonium, September guessed, working happily for his grandfather, the Municipal Library of Fairyland. Saturday would be visiting his grandmother, the ocean, every summer, and otherwise busy growing up, just as she had been. She felt no worry at all on that account. They would be together soon. They would discover what had happened to the shadows of the forest, and they would solve it all up in time for dinner the way her mother solved the endless sniffles and coughs of Mr. Albert’s car.

September set off with a straight back, her birthday dress wrinkling in the breeze. It was her mother’s dress, really, taken in and mercilessly hemmed until it fit her, a pretty shade of red that you could almost call orange, and September did. She fairly glowed in the pale glass forest, a little flame walking through the white grass and translucent trunks. Without shadows, light seemed able to reach everywhere. The brightness of the forest floor forced September to squint. But as the sun sank like a scarlet weight in the sky, the wood grew cold and the trees lost their spectacular colors. All around her the world went blue and silver as the stars came out and the moon came up and on and on she walked— very stalwart, very brave, but very much without encountering Pandemonium.

The soap golem loved the Marquess, though, September thought. And the Marquess is gone. I saw her fall into a deep sleep; I saw the Panther of Rough Storms carry her off. Perhaps there are no tubs to wash your courage in any longer. Perhaps there is no Lye. Perhaps Pandemonium stays in one place now. Who knows what has happened in Fairyland since I have been studying algebra and spending Sundays by the fire?

September looked about for the pink birds, of whom she felt very fond since they were her only company, but they had gone to their nests. She strained to hear owls but none hooted to fill the silent evening. Milky moonlight spilled through the glass oaks and glass elms and glass pines.

“I suppose I shall have to spend the night,” September sighed, and shivered, for her birthday dress was a springtime thing and not meant for sleeping on the cold ground. But she was older now than she had been when first she landed on the shore of Fairyland, and squared herself to the night without complaint. She hunted out a nice patch of even grass surrounded by a gentle fence of glass birches, protected on three sides, and resolved to make it her bed. September gathered several little glass sticks and piled them together, scraping away most of the lemony-smelling grass beneath them. Blue-black earth showed, and she smelled fresh, rich dirt. She stripped off glass bark and lay the curling peels against her sticks to make a little glass pyramid. She wedged dry grass into her kindling and judged it a passable job—if only she had matchsticks. September had read of cowboys and other interesting folk using two stones to make fire, though she remained doubtful that she had all the information necessary on that score. Nevertheless, she hunted out two good, smooth, dark stones, not glass but honest rock, and gave them a mighty whack, one against the other. It made a frightful sound that echoed all through the wood, like a bone bursting. September tried again, and again got nothing but a loud crack that vibrated in her hands. On the third strike, she missed and mashed one of her fingers. She sucked it painfully. It did not help to consider that the trouble of making fire was a constant one in human history. This was not a human place— could she not find a bush that grew nice fat pipes or matchbook flowers, or better yet, a sort of enchanter who might wave her hand and produce a crackling blaze with a pot of stew over it for good measure?

Nursing her finger still, September looked out through the thin mist and saw a glow off in the night, in the space between the trees. It flared red and orange.

Fire, yes, and not far!

“Is anyone there?” called September. Her voice sounded thin in the glassy wood.

After a long while, an answer came. “Someone, maybe.”

“I see you’ve something red and orange and flamey, and if you’d be so kind, I could use a bit of it to keep warm and cook my supper, if I should find anything to eat here.”

“You a hunter, then?” said the voice, and the voice was full of fear and hope and wanting and hating in a way September had never heard before.

“No, no!” she said quickly. “Well, I killed a fish once. So perhaps I’m a fisherman, though you wouldn’t call someone who only ever made bread once a baker! I only thought maybe I could make a mushy soup out of any glass potatoes or glass beans I might happen upon, if I was very lucky. I’d planned to use a big leaf as a cup for cooking. It’s glass, see, so it mightn’t burn, if I was careful.” September felt proud of her inventiveness—several things had gone missing from her plan, namely potatoes or beans or apples, but the plan itself held solid in her head. The fire was paramount; the fire would show the forest her mettle.

The red flamey glow came closer and closer until September could see that it was really just a tiny speck of a little coal inside a pipe with a very big bowl. The pipe belonged to a young girl, who clamped it between her teeth. The girl had white hair, white as the grass. The moonlight turned it silvery blue. Her eyes showed dark and quite big. Her clothes were all soft pale fur and glass-bark, her belt a chain of rough violet stones. The girl’s big dark eyes showed deep worry.

And in the folds of her pale hair, two short, soft antlers branched up, and two long, soft, black ears stuck out, rather like a deer’s, their insides gleaming clean and lavender in the night. The girl looked September over unhurriedly, her soft face taking on a wary, haunted cant. She sucked deeply on her pipe. It glowed red, orange, red again.

“Name’s Taiga,” she said finally, clenching her pipe in her teeth and extending a hand. She wore a flaxen glove with the fingers cut off. “Neveryoumind that mess.” The strange girl nodded at the lonely pieces of September’s camp. “Come with me to the hill and we’ll feed you up.”

September must have looked stricken, for Taiga hastened to add, “Oh, it would have been a good fire, girl, no mistaking it. Top craftsmanship. But you won’t find eatables this far in, and there’s always hunters everywhere, just looking for . . . well, looking to shoot themselves a wife, if you’ll pardon my cursing.”

September knew a number of curse words, most of which she heard the girls at school saying in the bathrooms, in hushed voices, as if the words could make things happen just by being spoken, as if they were fairy words, and had to be handled just so. She had not heard the deergirl use any of them.

“Cursing? Do you mean hunter?” It was her best guess, for Taiga had grimaced when she used it, as though the word hurt her to say.

“Nope,” said Taiga, kicking the dirt with one boot. “I mean wife.”

The Girl Who Fell Beneath Fairyland and Led the Revel There © Catherynne M. Valente 2012